How CIOs can raise their ‘IT clock speed’ as pressure to innovate grows

CIOs are facing pressure from the board to roll out IT projects increasingly quickly. How can they do that without running unacceptable risks?

I came across this article in the Computer Weekly based on cutting-edge research among leading businesses, such as CEB – formerly the Corporate Exectutive Board – and other industry experts which sums up the need for IT Speed and Agility very well indeed.” stated Craig Ashmole from IT Consulting CCServe Ltd.

Businesses are under pressure to radically rethink the way they manage information technology and the ability to introduce new technology quickly has become a boardroom issue.

More than three-quarters of business leaders identify their number one priorities as developing new products and services, entering new markets and complying with regulations, a CEB study of 3,000 business leaders has found. And the speed at which the IT department can respond to those demands is critical, says Andrew Horne, a managing director at CEB, a cross-industry membership group for business leaders.

“We are increasingly hearing from CEOs that their biggest concern is how organisations can change faster. The thing slowing them down and helping them speed up is technology,” he tells Computer Weekly.

Agile is not enough

The CEB – formerly the Corporate Exectutive Board – argues that traditional ways of managing IT are no longer able to meet the demands of modern businesses. Even agile programming techniques, which do away with long-winded development cycles in favour of rapid programming sprints, are not enough to get companies where they need to be.

A new model for IT is beginning to emerge, which is helping organisations speed up project roll-outs and free up reserves from maintenance to spend on innovative, high-impact IT projects.

Why the IT department needs a faster clock speed

IT departments have always been under pressure to respond more quickly to business demands.

Ten or 15 years ago, they hit on the idea of standardising their IT systems to cut down development time. Rather than roll out multiple enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems in different areas of an organisation, it made much more sense to roll out a single ERP system across the whole organisation.

That worked for CIOs back then, says Horne, but the emergence of cloud computing, analytics and mobile technology means IT can no longer keep pace with the demands of the boardroom. “Now the environment is so competitive. You have legacy systems, big data, analytic tools, technology for customers. You can’t standardise that. You can’t globalise that,” he says.

The rise of the two-speed IT department

Faced with this recognition, companies have opted for a two-speed approach, carving out specialist teams within the IT department to work exclusively on urgent projects.

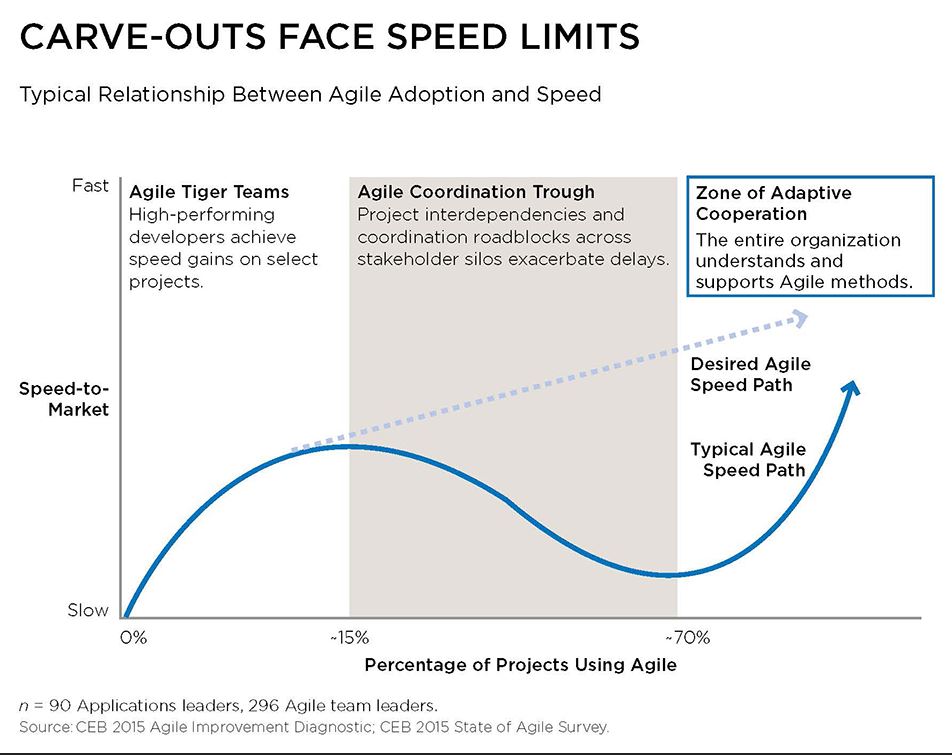

The fast teams, often dubbed “tiger teams”, focus on innovation, use agile programming techniques and develop experimental skunkworks projects. CEB’s research shows the idea has worked, but only up to a point. Once more than about 15% of projects go through the fast team, productivity starts to fall away dramatically.

We are increasingly hearing from CEOs that their biggest concern is how organisations can change faster. The thing slowing them down and helping them speed up is technology states Andrew Horne, from CEB

“You start off with agile tiger teams, top people, and they deliver at speed. They are glamorous, they get a lot of accolades from senior management,” Jaimie Capella, managing director for CEB’s US IT practice, told a masterclass for CIOs in October 2015. “And then we hit the valley of despair.”

Fast teams cannot work in insolation. They rely on other IT specialists in the slow team to get things done, and they need to work with other parts of the business that do work in an agile way. Once their workload grows, the teams find themselves dragged back by inertia in the rest of the organisation.

There is another problem too. As Capella pointed out, no IT professional with any sense of ambition will want to work in the slow team. “You create the fast team, give it a cool name, put it in new offices. Then everyone on the slow team wants to be in the fast team. That creates morale issues,” he says.

The emergence of adaptive IT

The answer that is beginning to emerge from this growing complexity is called adaptive IT. It allows the whole organisation to respond quickly to projects, if it needs to. CEB’s Horne describes it as “ramping up the IT clock speed”.

IT teams will either work at a fast pace or a slow pace, depending on the needs of their current project, and they will be comfortable changing between the two different modes of working.

What is IT clock speed?

IT clock speed is the overall pace at which IT understands business needs, decides how to support those needs and responds by delivering capabilities that create value.

“In any given situation the team can make a call whether speed is most important thing, and trade that off against cost or reliability,” says Horne. Building an adaptive IT department is difficult, and needs a radical rethink of the way CIOs manage their own part of the organisation and their relationships with the rest of the business.

Research by CEB suggests that 6% of organisations have made the transition, while some 29% are taking active steps towards it.

Eliminate communication bottlenecks

Companies can achieve the biggest improvements in IT clock speed by systematically identifying bottlenecks in the IT development cycle. Typically, the sticking points occur when agile IT teams collide with other parts of the organisation.

“Sometimes the problem is conflicting timelines. The IT team needs an architecture decision next week, but the architecture team only meets once a month. Or it needs an urgent risk review, but there is only one person in the organisation doing risk reviews,” says Horne.

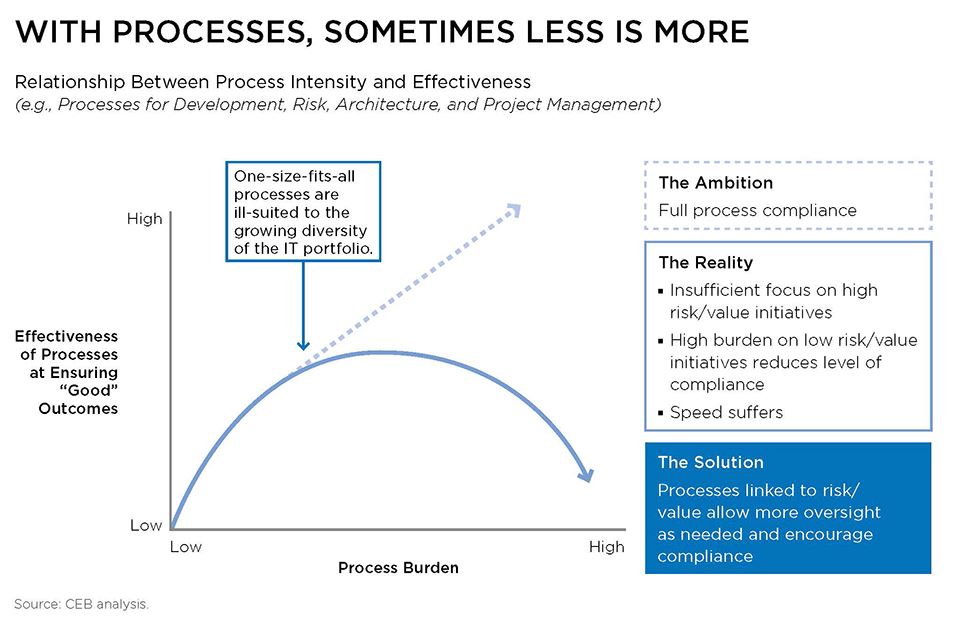

The next step is to minimise the red tape. As Horne points out, IT has become extremely process-orientated. Techniques such as ITIL and agile development are in fashion. “And for good reason,” he says. “It helps IT departments keep control.”

But how much process do CIOs really need? Adaptive companies have found they can manage with much less than they might think. They make streamlined processes the default. And if developers want something more rigorous, they have to argue the business case for it.

How CIOs can become faster

CEB’s research shows that CIOs can encourage a culture of speed by delegating more decisions. That does not mean losing control of IT, but it does mean setting clear goals and guidelines that allow other parts of the IT department to make their own decisions.

At the same time, CIOs need to think about the way they communicate with their IT teams. That might mean congratulating people on rapid delivery of projects, rather than focusing on the quality of the project. Horne poses the question: “What are the things on top of the IT score card – is it speed or reliability?”

If that sounds like a lot to do, it is. But companies can start off in a small way and still achieve some of the benefits. “It does not have to be big bang,” says Horne. The transition is not always easy. As one CIO put it: “The co-existence of agile with waterfall projects means we can’t devote people 100% to agile. People work two hours on waterfall, then two hours on agile. It’s hard to manage it.”

One mistake IT departments frequently make is to create a fast-track IT process and then “forget” to tell other parts of the business about it. “I can’t tell you how many times I have heard CIOs say they have a fast-track, but don’t tell business about it because then everyone will want it,” says Capella.

In other cases, IT departments have created such an onerous process for businesses to request fast-track IT – often involving answering questionnaires that can be hundreds of pages long – that business leaders simply don’t bother applying.

The benefits of IT triage

Those companies that have been successful at introducing adaptive IT have taken a cue from the medical world and are triaging their IT projects into streams of urgency.

One US company, for example, assesses each IT project against the following criteria:

- The value the business will gain if the project is rolled out quickly.

- Whether the risk of the project is contained.

- Whether it affects multiple areas of the company.

- How frequently the requirements are likely to change.

It has been able to speed up projects by creating self-service portals for urgent, frequently requested projects. They allow marketing people, for example, to create new marketing campaigns as they need them, without the need to wait for a developer.

Business professionals can also use pre-defined checklists to set specifications for commonly requested IT projects, which then go through fast-track development, with the minimum testing. Only the most business-critical systems which affect wide sections of the business go through a full rigorous development and testing process.

In another case, a large energy company has decided to do away with formal business cases for all but the most complex 10% of projects. It approves urgent, high-value projects as a matter of course. Non-urgent, low-value projects are simply not approved. A large consumer goods company has taken a different approach. It prioritises only projects that have the greatest impact on customer experience.

Adaptive IT increases efficiency

For those companies that have been able to take up the adaptive model, CEB’s research shows the benefits can be huge. Business can typically roll out a project 20% more quickly – a saving of one month on a six-month project.

They also have more freedom to re-allocate cash to the most urgent projects. Traditional IT departments can re-allocate about 15% of their budget if a new project comes up. For adaptive organisations, the figure is 40%.

“Adaptive organisations are also more efficient. If you have a £100m IT budget, they are spending £2m less than average on IT legacy systems, which means they are spending more on collaboration, cloud and big data,” says Horne.

The pressure for IT to become faster is coming down from the CEO and their fellow board directors. “They are frustrated at how slow the company is changing. When they ask why it’s slow, technology is coming up as the answer,” says Horne.

But to succeed, organisations require a strong CIO, with strong leadership skills. “It needs someone willing to lead change rather than just keep IT stable; someone who can work well with business leaders and communicate with their teams. If you are an old-style CIO, interested in technology, keeping the lights on, you are going to be in trouble,” he concluded.

Having spent a majority of my career working with and supporting the Corporate CIO Function, I now seek to provide a forum whereby CIOs or IT Directors can learn from the experience of others to address burning Change or Transformation challenges.